Who was Titus Lombardy?

Titus was a black man of West African descent, born into slavery in Southold, Suffolk county, Long Island, New York around 17731, shortly before the start of the American Revolutionary War there with the Battle of Long Island.

His story, as presented here, is pieced together with careful research of genealogical and historical records.

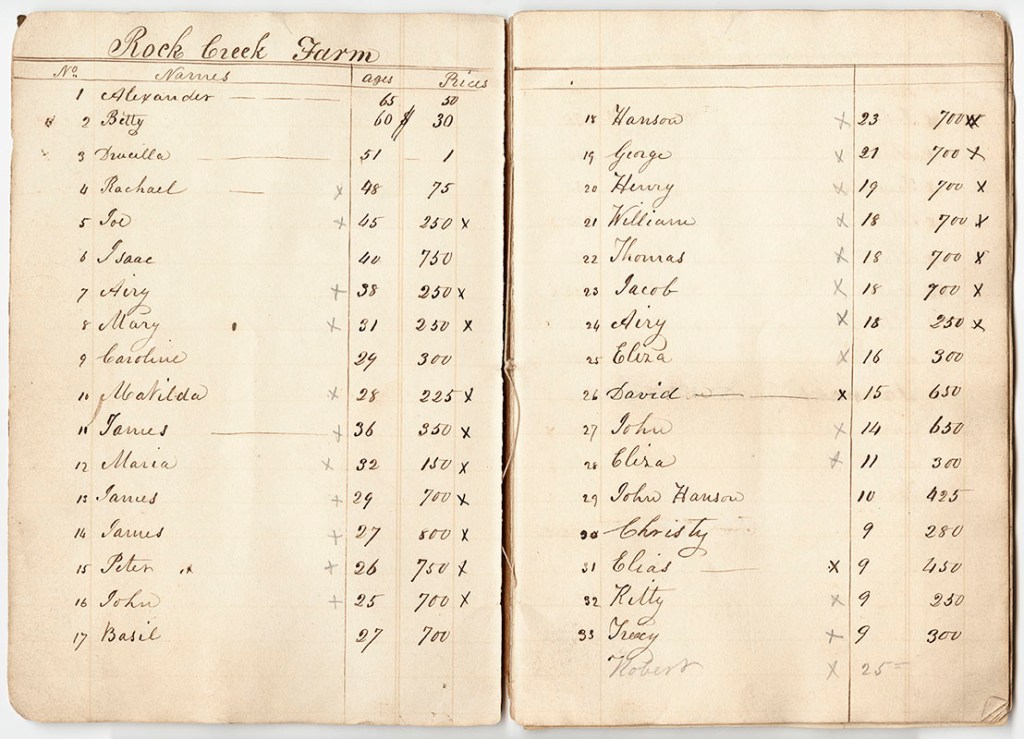

Most of the history of American slavery has been written from the perspective of the enslaver, so I prefer to provide more of Titus’ backstory. Unfortunately, there is very little.

Due to the nature of slavery’s entwinement of human lives, we must examine the details of the enslaver’s life to gather more clues about the enslaved person. This scarcity of documentation about enslaved persons is yet another facet of the profound dehumanization enacted against them, with multi-generational impact.

Enslaved people had very little agency over their existence, and few permanent records were kept of their life events and relationships. The ability to trace one’s ancestry back more than five generations is largely a feature of white privilege in comparison to what is available to descendants of Africans who were brought to America against their will.

Who Were Titus’ Parents?

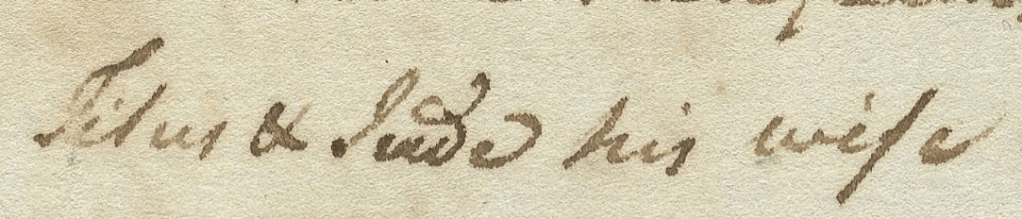

Titus was the son of Titus and Jude, enslaved by Ezra L’Hommedieu of Southold, New York.2 According to the records First Presbyterian Church of Southold, Titus was baptized on 22 August 1773.3 He had an older brother Linus, born about 1768,4 and a younger sister Eunice, born about 1775.5

Titus was relatively fortunate in that he apparently knew his family of origin. In other regions of the United States, enslaved children and infants often were separated from their parents, inflicting untold anguish and intergenerational grief on the families. This robbed the children of not only the nurture of a loving home, but also their sense of connection and belonging that comes from human family bonds.

DNA sampled from known descendants indicates Titus and his ancestors originated from the West African coastal region which was central to the Atlantic slave trade routes: Ivory Coast, Ghana, Togo, Benin, Nigeria, Cameroon, and Congo.

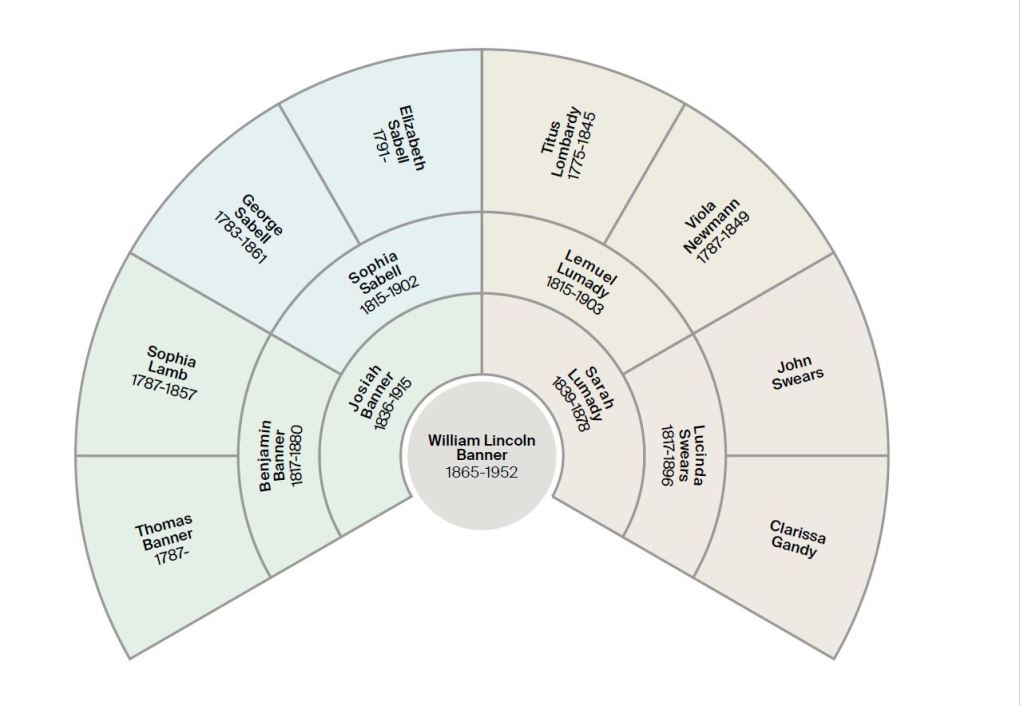

Family oral tradition passed down from his great-grandson (and my great-grandfather)

William Lincoln Banner (1865-1952) of New Britain, Connecticut, said that Titus was Jamaican. While there are no records to support or disprove this idea, it is plausible that one or more of Titus’ forebears lived in Jamaica at least temporarily as it was another central point in the tri-cornered Atlantic slave trade route.

Click image to enlarge.

Click map to enlarge.

Who Enslaved Titus?

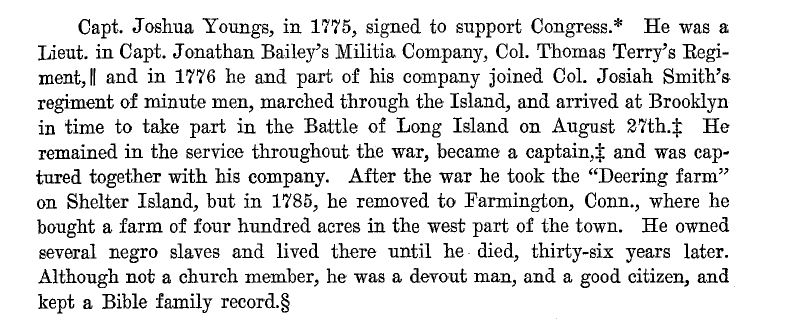

Titus Lombardy was enslaved by Capt. Joshua Youngs, a man of English descent and an officer in Gen. George Washington’s army.

Youngs was a member of the sixth generation of his family to live in Suffolk County, Long Island, New York. 6 The Youngs family had wealth, land, and political influence, with many members serving in leadership in the fields of commerce, law, the military, and religion.

Capt. Youngs rose quickly in military ranks, going from militia and minuteman to the Continental Army. He served alongside (but is not known to have participated with) members of the Culper Spy Ring, dramatized in the AMC period drama television series Turn: Washington’s Spies. The series opens with a scene of an infant who would have been about the same age of Titus at the time.

How Did Titus Get His Last Name?

Many enslaved people had only a first name, given by their enslaver, and were sometimes known by the enslaver’s last name. Names often changed as the enslaved people were moved between enslavers’ households.

“Titus” was a name commonly given to enslaved men, but the origin of the name “Lombardy” is puzzling, because we might expect him to be called “Titus Youngs” after his enslaver.

Where did the name Lombardy originate?

Records from First Church in Farmington, Connecticut may shed some light on the matter. Transcriptions of the church membership rolls are grouped under headings, by surname, and whenever there are variant spellings the variants are combined in the heading. For example, Titus is listed under a heading the contains the names “L’Hommedieu, Lammady, Lommady, Lemmedieu, Lummady“.7

It is interesting to note that Ezra L’Hommedieu and his family, also from Suffolk County, New York, were neighbors and associates of Capt. Youngs’ family when they lived on Long Island.

Records of L’Hommedieu’s life indicate he enslaved a number of black persons in his household. At the outbreak of the Revolutionary War, L’Hommedieu, along with many other local residents, took refuge in Connecticut.

Titus was an infant at the time. One plausible explanation is that he was born in the L’Hommedieu household, was deemed too young to travel in conditions of war, and was sold or given to Youngs by L’Hommedieu as he prepared to flee.

The formal, French-inflected pronouncition of “L’Hommedieu” would become “Lombardy” or “Lummady” in the mouth of the working man.

How Did Titus

End Up in Connecticut?

Titus’ enslaver, Capt. Youngs, lived in Southold on Long Island and fought in the initial battle the Revolutionary War, known as the Battle of Long Island, or Battle of Brooklyn, which broke out essentially in his back yard.

In 1785, shortly after the war ended, Youngs moved his household to Farmington, Connecticut, taking 2 black enslaved males with him.8

Titus was only 10 years old at the time, and there is no record that would indicate either of his parents relocated with him.

How Did Titus Gain His Freedom?

In the book The Memorial History of Hartford County, Connecticut, 1633-1884 vol II we read the account of Capt. Youngs appearing before “one of the civil authority and two of the Selectmen” of Farmington on January 10, 1816 to issue emancipation to the man he enslaved, Titus, age 41.9

The original letter of manumission is in the possession of the Farmington Historical Society.

Federal census10 and local church records11 indicate that Titus was already living separately from the Youngs household, raising a family independently at the time he was manumitted.

It is not clear whether Titus was required to provide payment for his release. But we do know that Connecticut and local regulations required any person released from enslavement to be of sufficient good health, age, and resources as to enable them to earn a living separate from their former enslaver. Otherwise, former enslavers were required by law to provide housing, clothing, food, and medical care for the young, elderly, and infirm released from enslavement.

“Whereas, on application made by me, Joshua Youngs, of Farmington in Hartford County, to one of the civil authority and two of the selectmen of said Farmington, they have signed a certificate that Titus, a black man, now or late my slave, is in good health and not of greater age than forty-five years, nor of less age than twenty-five years, and upon examination of said Titus they are convinced that he is desirous of being made free.

“Therefore be it known to all whom it may concern, that I have and hereby do completely emancipate and set at liberty the said Titus, so that neither I, or any claiming under me, shall hereafter have any right whatsoever to his services in virtue of his being my slave.

“Done at Farmington this 10th day of January AD 1816

“Joshua Youngs

“In presence of John Mix, Samuel Cowls

“John Mix, Register”

What Does “Manumission”

Mean?

Manumission means setting a person free from slavery or servitude through legal means, such as a written document or a formal process. It’s about giving them their freedom and rights.

Connecticut’s Gradual Emancipation Act of 1784 required enslavers who chose to free the people they enslaved to support them if they were unable to care for themselves. 12

This law reflected a concern among some lawmakers about the welfare of newly freed individuals who might not have the means to support themselves after emancipation.

The law in Connecticut, along with similar laws in other Northern states during the late 18th century, required enslavers to financially support or establish bonds to prevent their freed enslaved individuals from becoming a burden on the state or community.

These laws aimed to manage the transition to freedom while balancing freedom and responsibility, with specific requirements differing from state to state.

Why Was Titus Released From Slavery?

A Tale of Two Cities: Farmington, CT and Southold, NY

The question of why Titus was released from enslavement is open to conjecture. Some educated guesses can be made, however, when we compare the social atmosphere of Suffolk County, New York with that of Farmington, Connecticut in the 18th and early 19th centuries.

It may be surprising for some to learn that Long Island was once a key point in the northern U.S. for the Atlantic slave trade route. In fact, American slavery originated in New York in 1626 with the importation of 11 enslaved African men by the Dutch West India Company to New Amsterdam (New York).

Local history indicates the people enslaved in New York encountered working conditions that generally were less harsh than enslaved persons in southern states, Brazil, and the Caribbean, and sometimes lived in the same house as their enslavers, working side-by-side with them. Nevertheless there was an inhumane assumption of “other-ness” from white persons toward black persons, to the point that infants and young children such as Titus might be forcibly separated from their parents.

When contrasting this with Farmington’s vibrant abolitionist sentiment and the humanistic, inter-racial openness of First Church, it is easy to see Capt. Youngs was immersed into a wholly different local mindset when he set up household in Connecticut. First Church membership rolls include numerous black, indigenous, and mixed-race individuals and families. Youngs and Lombardy both appear on the roll, along with their families.

It may be jarring to consider, but it is entirely possible that Youngs and Lombardy sat under the same church roof, listening to the same abolitionist-minded preachers holding forth on the grave wickedness of enslaving fellow humans.

It is likely that the change of setting, along with Young’s exposure to Farmington’s abolitionist activists, had great influence in changing his mindset toward slavery and human dignity.

Courtesy of Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, CONN,2-FARM,2-3.

What Did Titus Do After He Was Freed?

It is likely Titus earned his living as a farmer or general laborer, given that he grew up working on Youngs’ 400 acre farm and woodlot in Unionville, Connecticut (the western section of Farmington).

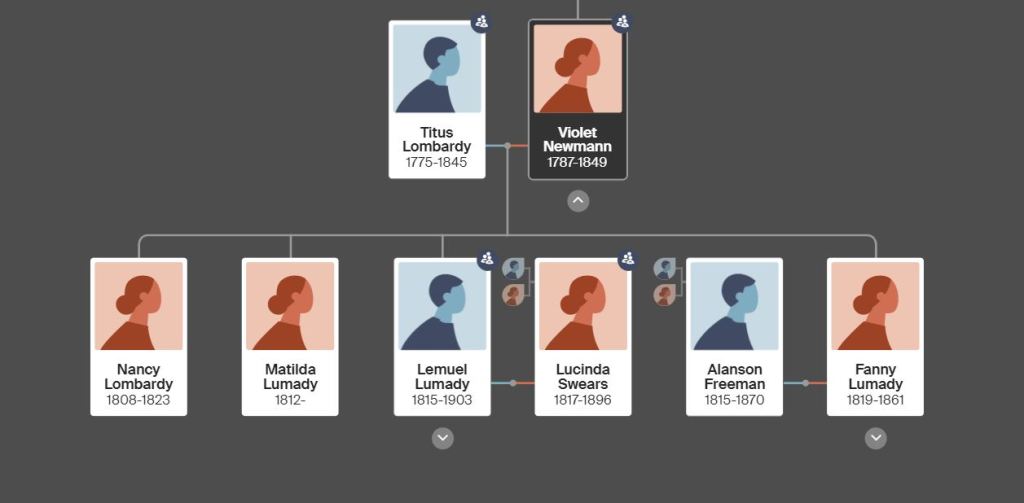

Titus settled down in Farmington and made a home with Violet Newmann from Chester, Connecticut. 14

Titus died at the age of 70 in Farmington in 1845. Violet died four years later at the age of 62 in New Britain, CT in 1849.15

He spent the first 41 years of his life enslaved, and the following 29 years as a free man.

Who Were the Children of Titus and Violet?

Titus and Violet had four children:

Nancy (1803-1823) who died in Farmington on April 16, 1823 at the age of 15.16

Matilda (b. 1812) never married, and lived with her younger sister Fanny after their parents died. 17

Lemuel (1815-1903) who moved to New Britain and raised a family;18

Fanny (1819-1861) who married Alanson Freeman (1815-1870) in 183819, raised a family in Farmington.20

It is interesting to note that only Titus and three of their four children are named in the membership roll of 1st Church Farmington. Violet’s name does not appear, nor does Matilda’s, and there are no marriage records for the couple. But the 1850 federal census mortality21 schedule for New Britain names Violet as the wife of Titus.

From Ruth Backhaus van Wijk’s Ancestry.com family tree.

How Can I Learn More About Titus Lombardy?

If you are a STUDENT, you can learn more about Titus by studying the environment he lived in and the friends and neighbors he associated with.

If you are interested in the descendants of Titus, you may view his family tree on FamilySearch.

- First Presbyterian Church (Southold, N.Y.), Titus, p. 130, 22 Aug. 1773; digitized and accessed at Ancestry.com. ↩︎

- “Last Will & Testament, Inventory, Executors, Power of Attorney – Ezra L’Hommedieu Estate: 1789-1823,”digitized and accessed atN.Y. University, Fales Library and Special Collections, (https://findingaids.library.nyu.edu/fales/mss_208/images/7pvmd3fh/), Image 6. ↩︎

- First Presbyterian Church (Southold, N.Y.), Titus, p. 130, 22 Aug. 1773; digitized and accessed at Ancestry.com. ↩︎

- First Presbyterian Church (Southold, N.Y.), Linus, p. 121, 28 Aug. 1768; digitized and accessed at Ancestry.com. ↩︎

- First Presbyterian Church (Southold, N.Y.), “Baptisms, Marriages, and Deaths, 1749-1832,” Eunice, p. 134, 26 March 1775; digitized and accessed at Ancestry.com. ↩︎

- Selah Youngs, Jr., Youngs Family: Vicar Christopher Yonges, His Ancestors in England and His Descendants in America, (New York: Youngs, 1907), 151; digital image, Internet Archive; (https://archive.org/details/youngsfamilyvica00youn/page/151/mode/2up : accessed 22 May 2022). ↩︎

- Connecticut, US, Church Record Abstracts, 1630 to 1920, vol 034 Farmington, media, Ancestry.com (https://bit.ly/3P7nhNw : accessed 10 Jun 2022). ↩︎

- Youngs, Youngs Family, 151. ↩︎

- J. Hammond Trumbull, editor, The Memorial History of Hartford County, Connecticut, 1633-1884 vol II pp.199-200. Internet Archive, (https://archive.org/details/memorialhistoryo02trum/page/198/mode/2up : accessed 2 Jun 2022), 198-199. ↩︎

- 1810 U.S. census, Hartford County, Connecticut, population schedule, Farmington, for Titus Lombardy and Joshua Youngs; digital image, Ancestry.com (https://bit.ly/3Njt556 : accessed 10 Jun 2022); from Family History Library Film: 0281229, Roll: 1; Page: 407; Image: 00407. ↩︎

- Connecticut, US, Church Record Abstracts, 1630 to 1920. ↩︎

- Menschel, David. “Abolition without Deliverance: The Law of Connecticut Slavery 1784-1848.” The Yale Law Journal, vol. 111, no. 1, 2001, pp. 183–222. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/797518. Accessed 5 Sept. 2023. ↩︎

- Acts and Laws of the State of Connecticut, in America. Hartford: Hudson & Goodwin, 1805. Original from the New York Public Library. Digitized June 17, 2009.(https://bit.ly/3Pzp3Kx : accessed 9/4/2023. ↩︎

- “Lemuel Lumady,” New Britain Herald. ↩︎

- 1850 U.S. census, Hartford County, Connecticut, mortality schedule, New “Britain”, p. 122 (stamped), line 13, Violet Lumady; digital images, Ancestry.com (https://bit.ly/3yaBGli : accessed 10 Jun 2022); citing NARA microfilm publication T655 (Washington, D.C.). ↩︎

- Connecticut, US, Church Record Abstracts, 1630 to 1920. ↩︎

- National Archives, Resources for Genealogists, Census Records, “1810 Federal Census form”, Archives.gov (https://www.archives.gov/files/research/genealogy/charts-forms/1810-census.pdf : accessed 2 Jun 2022). ↩︎

- “Lemuel Lumady”, New Britain Herald. ↩︎

- Connecticut Town Marriage Records, pre-1870 (Barbour Collection), Farmington, Connecticut, 1838. Microfilm, Connecticut State Library, Hartford. ↩︎

- 1850 U.S. Census, Hartford County, Connecticut, population schedule, Farmington; Ancestry.com (https://bit.ly/484fvhx : accessed 19 Jun 2022), Alanson Freeman, line: 8, Roll: M432_40; Page: 336A; Image: 95. ↩︎

- 1850 U.S. census, Hartford County, Connecticut, mortality schedule, New Britain, p. 122 (stamped), line 13, Violet Lumady; digital images, Ancestry.com; citing NARA microfilm publication T655 (Washington, D.C.). ↩︎